Episcopally Led and Synodically Governed

Churches throughout the Anglican Communion describe themselves as “Episcopally Led and Synodically Governed”. This phrase is an attempt to acknowledge the special authority of Bishops while embracing a more democratic understanding of Church life.

In many ways, the “Episcopally Led and Synodically Governed” formula is a triumph of Anglican compromise. It was used most effectively by Bishop Michael Turnbull and his working group in ‘Working as One Body’ published by the Church of England in 1995. It allows us to reap the benefits that can be found in both powerful individual leaders and rich democratic processes – but it also generates a potentially serious conflict given the fuzziness of the word “leadership” and the inevitable conflict this creates.

In recent years there has been a move to adopt more professional models of leadership and management in the Church of England. Those in favour of this move see it as a way of equipping and releasing gifted leaders to do the work of God. Opponents accuse the hierarchy of ever-increasing managerialism.

I believe that the solution to this conflict can be found in our Anglican ecclesiology and a more pneumatological approach to leadership.

But first I want to look again at what we mean by “leadership” and how that leadership is exercised. We need to clarify what we mean when we use this word before we can think more clearly about how it is exercised.

Defining Leadership

In popular imagination “leaders” are quasi-heroic figures with unique characteristics and a destiny to fulfill. We tell stories of leaders like Churchill, Hitler, Roosevelt, Thatcher, Mandela, Ghandi or Putin. Famous leaders like these generate powerful mythologies which mold our thinking. We associate “leadership” with ideas of struggle, power, persistence, or success against overwhelming odds. Few of us could achieve the impact of these heroes and villains, but they provide unconscious models which shape our own behavior and expectations.

It is also common to think that “leadership” only exists in relation to organisational roles. In other words, “leaders” are people in positions of seniority – head teachers, CEOs, presidents, prime ministers or bishops. Some people do have “positional authority” which gives them a right to exercise particular powers or make certain decisions – but this should not be confused with leadership as a general concept. There is a genuine relationship between leadership and organisational position, but it is not straightforward.

Those who study leadership generally define it in terms of influence and relationships. For example, Chemers (1997. An integrative theory of leadership. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.) describes leadership as “a process of social influence in which a person can enlist the aid and support of others in the accomplishment of a common and ethical task”. The task of leadership is to encourage or persuade others to think, behave or act differently. As the Community Organisers of Citizens UK like to remind us, “leaders have followers”.

People with status or position do have access to “levers of power” which enable them to exercise their leadership in a more effective way. Bishops, for example, have the power to chair and convene meetings, make appointments, or issue licenses. They can pick up the phone – and expect a reasonable number of people to answer.

There are, however, limitations on the control that positional leaders are able to exercise. These limitations can be personal, moral, legal, systemic or practical – but they do exist. Positional leadership does not give people god-like power – whatever some may think.

It should be noted that many leaders do not have positional authority at all. They lead through force of personality, articulate communication or simple popularity. Many conflicts have begun when a positional leader overestimated their own power and underestimated the things that relational leaders or “little people” can achieve by working together.

Leadership is a complex issue, but we are going to use the following definition for this discussion:

Leadership is influence exercised through social relationships,

with the aim of achieving action or change.

The Kingdom, the Spirit and the Mind of Christ

As a Church, we need to have a concept of leadership which coheres with our theology. We are disciples of Christ, and our ultimate aim is life with Jesus in the emergent Kingdom of Heaven. Our leadership must have the Kingdom as its ultimate goal, and we must exercise it in a way that honours Christ.

In the New Testament, leadership is a gift of the Holy Spirit, given for the building up of the Church. It requires humility, moral integrity, self-sacrifice, and a commitment to the good of others. The purpose of leadership is to nurture disciples, ensure good order, and seek the well-being of God’s people.

The Holy Spirit has a central role in leadership because the Spirit works through God’s people, revealing the Word of God. The Holy Spirit blows where it wills, so it is important to listen for what the Spirit is saying to the churches.

It is crucial to note that there are people in formal positions of authority within the New Testament community, but the Holy Spirit is not limited to people with identified roles. God speaks through the Apostles but also through deacons, women, slaves, and gentiles. When the Church gathers, it is possible to have words of prophecy or the interpretation of tongues. These are spoken by multiple speakers, while others discern what God may be saying.

Throughout history, God has chosen to work through unexpected people. The gift of leadership is given to the Church through the work of the Holy Spirit – and the Spirit is not limited to those in high office.

This raises a serious challenge for the Church, but it is a familiar one, and it has been faced throughout Christian history. The Rule of St Benedict, for example, challenges us to see Christ in all people – even those we find difficult. Their voice may bring the Word of God that we most need to hear. As Anglicans, our concept of being “synodically governed” is a nod in the same direction.

If leadership is influence, then it is the influence of Christ through the Holy Spirit that we most need in the Church. If the Spirit is active in every believer, then each and every believer is a person through whom the Spirit could exert influence. There is no theological justification for limiting our concept of leadership to those in hierarchical positions. Leadership is given through everyone for everyone.

The Levers of Power

Leaders achieve influence through three main activities which we could describe as “levers of power”:

- Control: It is easy to confuse leadership with control – particularly when it comes to positional leadership – but control is merely a tool that leaders can use. All people have some measure of control, even if it is only over their own actions, thoughts or words. Positional leaders may have more resources that they can control, or more people that they can command – but their control has limited impact if there is no trust, or the people do not believe in their project.

- Relationship: The impact of leadership is vastly increased if it is backed up by trust, understanding or personal commitment. Followers appreciate leaders who they can relate to on a personal level. Leaders therefore need to invest time in the people that they want to lead. This often means listening to the real concerns of other people and looking for ways to address them.

Good leaders are good with people.

- Information: Knowledge is power, so those who control the flow of information have a built-in advantage when it comes to leadership. They can influence others by the way they communicate, and by what they choose to share – or not to pass on. We should not underestimate the power of gatekeepers when it comes to information. Knowledge is not neutral; it is always curated.

In every organisation or community there are disparities between people with greater or lesser access to these three levers of power. It is worth noting, however, that we all have some level of control. We all have relationships with others. We all communicate information in some way. We are all leaders – whether we are aware of it or not.

Measuring Leadership

A few years ago, I carried out a small research project which aimed to look at collaborative leadership in Christian communities. When I started the project, I wondered whether churches could be compared to computers with mechanisms for input, output, memory and processing power. I soon realised that a better analogy was a network – with each node exercising a level of leadership in relation to all of the others.

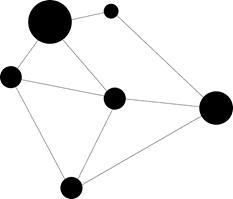

A church is a community of people linked together by a web of relationships. It’s possible to illustrate this using a network diagram which describes the way individuals are held together. Here is a simple example:

In this example, the dots represent people, and the lines represent the relationship between them. The dots vary in size according to the relative influence or power that different people have. The lines indicate relationships which could be measured in terms of time spent together or the frequency of contact.

It’s immediately apparent that each person is different in terms of relative power or the number of connections that they have. This has an impact on their ability to lead.

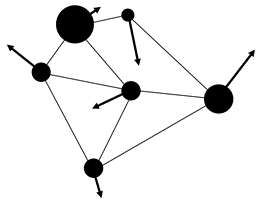

Leadership is often defined in terms of influence. It’s the ability to influence the thoughts and behaviour of other people. In this simple community, each person could be thought of as a leader. They can all influence the people around them. I like to demonstrate this by drawing arrows, to indicate the relative influence that each person has:

The arrows are pointing in different directions, to indicate that each person is pulling in the direction that they believe the group should go. Some arrows are longer than others, because people put varying amounts of energy into leadership. Some people are very determined, while others are a bit uncertain. Everyone is part of the community however, so everyone has some form of influence on those around them.

The danger is that people are pulling in so many different directions that the group doesn’t go anywhere fast. In fact, the different forces can easily cancel each other out so the community doesn’t go anywhere at all!

There is a wonderful phrase in the Book of Proverbs and it often gets quoted when people talk about leadership: “Where there is no vision the people perish” (Proverbs 29.18). The implication is that a community needs a strong sense of direction or purpose if it is to flourish or even survive. Without a vision the people might perish, but with too many visions they are completely lost!

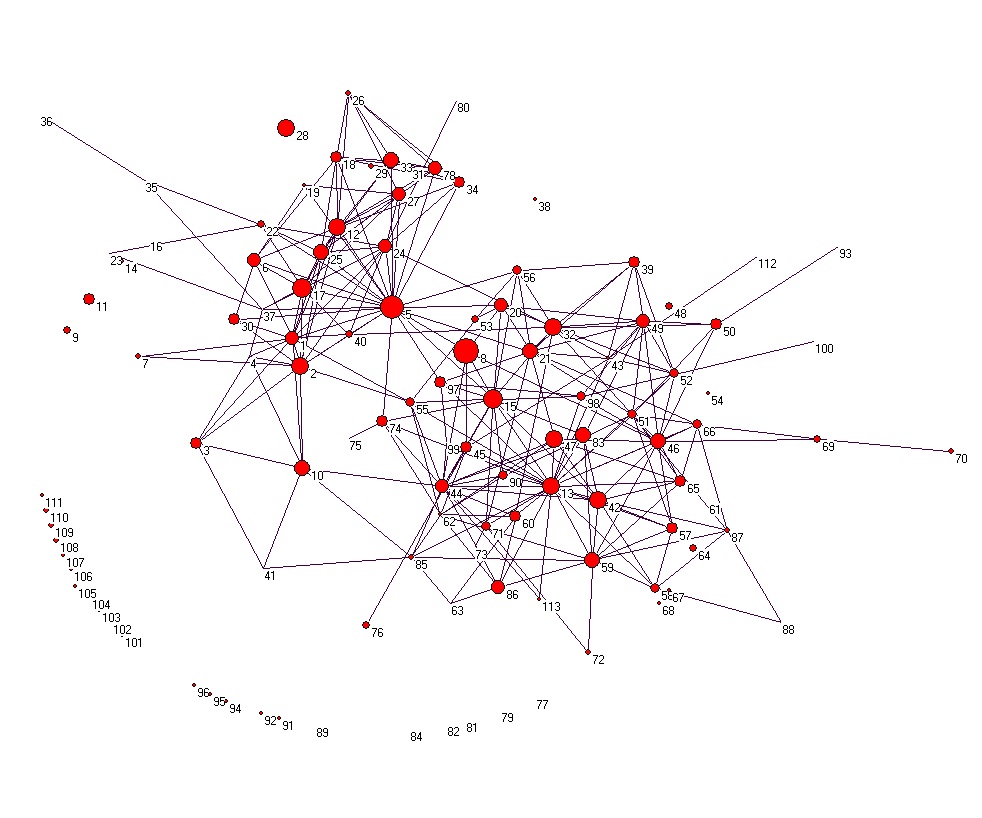

With this theoretical model in mind, my next step was to map leadership within real-world congregations. I used simple questionnaires that enabled me to measure the perceived influence of individuals within the network – asking people to name the six people they spend the most time with, and the six people they get most information from. Using the mathematical tools of Social Network Analysis, I was able to gain real insights into the way these congregations worked. Here is an interesting example:

Without knowing the name, denomination or location of this church, there is a lot that this “map” reveals. We can see at least two subsets of people… There are also a number of more connected people…. Some dots are larger than others, indicating a greater level of power… There are a few branches or bridges…. What is going on here?

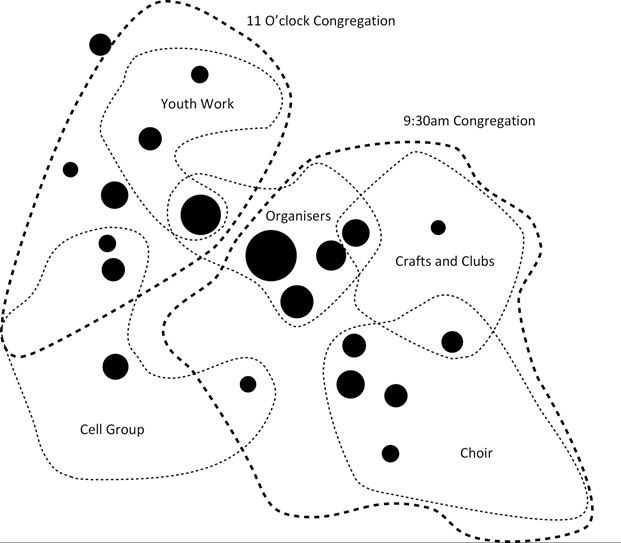

I interviewed members of this church and was able to make more detailed observations. Participant number 5 was a churchwarden who acted as the main bridge between two Sunday morning congregations. Number 15 was the other churchwarden but she was more embedded in one specific congregation. Number 8 was an ex-minister who was still in the area. There were also a number of small groups including a choir, a youth group, a cell group and a craft group. All of these elements can be seen in the “map”.

The following diagram illustrates the subsets in the church, revealing the connections between groups and individuals:

This exercise provided a fascinating window into the patterns of leadership and relative power in a fairly normal Christian community. It shows that leadership can be dispersed throughout congregations with a number of key leaders acting as influential hubs or links.

Furthermore, my research hints at the fractal nature of leadership within networks. In other words, similar patterns are observed at every level in the community, from the local church choir, to the congregation, and (by implication) to parishes, deaneries, dioceses, provinces and beyond.

I found two main patterns in my research. I tend to describe them as “eggs” or “starfish”.

“Eggs” have a strong core and an impermeable boundary. This pattern tends to emerge when one person (sometimes with a close-knit team) becomes the central focus of leadership. Everyone belongs because they are in relationship with the leader. This is a strongly pastoral model with many attractions. It provides coherence, consistency, and clarity in terms of roles, vision and belonging. Unfortunately, the relational capacity of the leader and the core team limit “eggs”. There is a limit to the number of people that the main leader can hold in relationship. It can also be difficult to break into the community, since the members tend to be inwardly focussed and prevent the leader from making new connections.

“Starfish” are more complex. Leadership is more dispersed, and each limb has its own “brain”. The different arms of the body vary in size and can provide opportunities for new members to be integrated and find a home. This pattern has strengths in terms of flexibility, openness and diversity, but it requires a willingness to work in partnership with others. Moreover, the positional leaders must have skills in collaboration and team work or the whole community will pull itself apart. The potential for growth is very real – if only people can work together!

Reimagining Anglican Ecclesiology

The Church of England is an episcopalian body. Our ecclesiology is often visualised in hierarchical terms with bishops at the top and the laity at the bottom. Leadership comes from those at the top, and others are expected to follow…

Putting aside for a moment the things Jesus said about the first coming last and the last coming first, this picture doesn’t reflect what we know about leadership in a Christian community. If leadership comes from the Holy Spirit through everyone to everyone; if everyone is a leader and everyone is a follower, this rigid hierarchy is a poor reflection of who we really are.

I would like to suggest that episcopalianism is better understood as a network rather than a hierarchy. Bishops are utterly crucial to who we are because they are the relational nodes that hold us together – rather than the managers who tell us what to do.

Their authority comes from the depth and diversity of their relationships, not a questionable sense of being “better” than others in the Church family.

A new bishop said to a friend of mine that he felt like an imposter and wasn’t ready for the role. My friend said, “that’s because you aren’t ready and you are an imposter – but that will change.”

When the church sets someone aside as a bishop, we also put them in a position where they can build the relationships which will enable them to serve in this key role – holding the church together and ensuring that the Good News entrusted to the Christian Community is shared and proclaimed.

The same is true of all of us who serve as link people in the Body of Christ: archbishops connect bishops and dioceses, archdeacons connect archdeaconries, area/rural deans connect deaneries, rectors and vicars connect the people in parishes with the wider church. We belong because we are in relationship with others.

This may sound like an esoteric argument, but it’s crucial to the way we understood the “episcopally led” formula. Leadership is not a right that comes through status, but a consequence of the entire network. It is an emergent phenomenon. It is not something that is conferred on a small number of individuals, but the sum total of the Spirit at work amongst all God’s people.

I want to reaffirm the phrase “episcopally led and synodically governed” because it speaks to me of the church that we are called to be. True episcopal leadership is leader-rich, dynamic and open. It is fundamentally relational.

Remember the observation that starfish have potential to grow while eggs are stuck within their shells. Centralised leadership often causes us to turn inwards, but God wants us to spread out into the wider world, bringing healing, transformation and hope. Perhaps it’s time for us to break out of our shells?