An Exploration into the Roots of Relationality

Pilate asked, ‘What is truth?’ (Jn 18:38)

Jesus said, ‘I am the way and the truth and the life.’ (Jn 14:6)

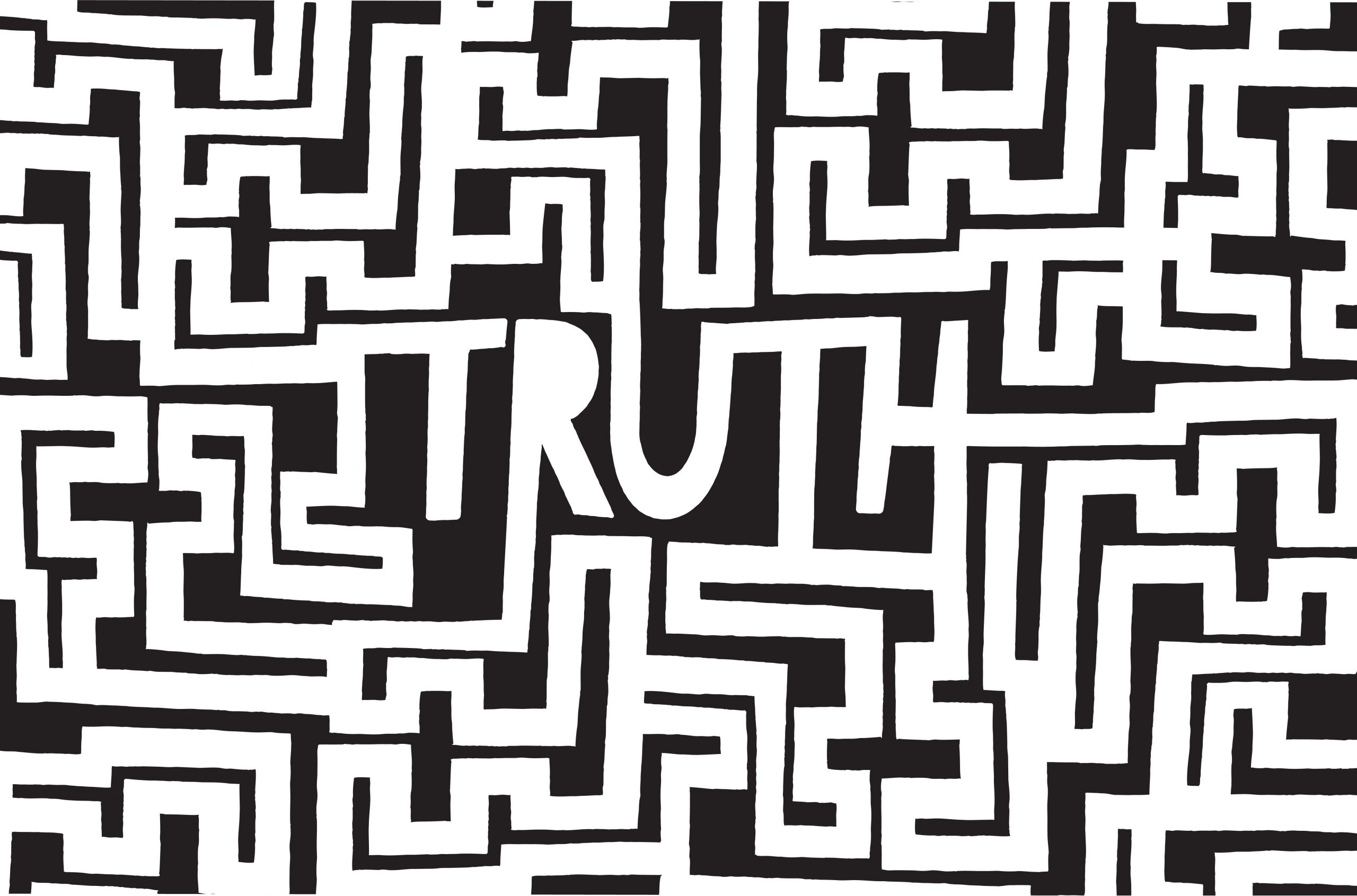

It is not uncommon for unity and truth to conflict. Either we stick to our beliefs and break relations with those who think differently, or we compromise to maintain harmony. This has been one motor for Christian division and the breakup of Christ’s Church. It is a challenge frequently faced by the Anglican Communion and within the Church of England. The pattern of thought behind the danger of division, in whatever context it occurs, is to seek truth through a debate that strives to persuade our opponents that our thinking is sounder than theirs. Various ploys are used: appeal to authority, demonstrating our logical coherence and reasonableness, pointing out the flaws in the opponent’s argument, displaying the attractiveness of our views and the good that comes from them or even (less often in church contexts fortunately) trying to discredit our opponent so that the veracity of their position is put in doubt. It is a mini war, however amicably it can, sometimes, be conducted. Nonetheless, this kind of debate contains much that is good: it harnesses disagreement, holding out the hope of finding, in the winning argument, a perception of truth.

But it is a highly risky procedure, and a knockdown conclusion hardly ever happens. For it is rare that anyone changes their mind; indeed, to do so may seem like betrayal and smack of moral deficiency. Or, as is more often the case, the contest ceases to be about seeking truth but simply a matter of striving for victory. The conflict of truth and unity, in the white-hot heat of discussion, easily drives people apart and, as relationships come to be destroyed, separation deepens and what is at issue changes. Not only does the ongoing lack of agreement mean that truth has not emerged but, still more, in the ensuing battle it is increasingly less likely to. This confusion shows that the truism is true: truth is the first casualty of war.

I want to suggest that there is another way of finding truth, one that can encompass debate but that goes far beyond it. It comes to effect in human relationality, but it is rooted in a deeper, prior relationality at the heart of reality itself. Hence, while this other way demands enhancing how we relate to one another, so dispensing with the martial connotations of adversarial debate, it cannot be reduced to that. This other way is not merely a matter of disagreeing more efficiently, good as that may be in itself, but enters a new dimension where there is a better relationship with truth.

Truth is a person

To see how we can find truth in a better way, we have first to ask what is the truth we seek? In the first instance, we are seeking to discover ‘that which is the case’. The better way of seeking this, I hope to show, is present in what we do when seeking for truth in a deeper sense. For beyond truth defined as ‘that which is the case’, there is the truth about how things are, about their nature, which includes their purpose and meaning and, with these (if they have them), there is an ethical claim. It is this truth that can provide a better way also of finding out ‘what is the case’ in other contexts.

It is, of course, entirely possible to claim that the truth about how things are is that they are present to our consciousness and have no further meaning or intrinsic purpose. This denial is a more complex statement than it may seem. It is an interpretation filtering the view of things through a lens that assumes there is no meaning or purpose, which is an ideological stance as much as any view that posits these things. Cross-culturally, indeed, the intuition has generally been that there is a truth about things to be discovered, even though this same pattern of thought takes on a wide variety of forms – from the mythologies of many cultures to notions such as the Tao in China, ṛta in India, logos in various currents of Greek thought. Christianity too has its version of this intuition, rooted in the historical encounter with a person, Jesus, which gave a particular slant to the use of the term logos within Christian circles. It is this Jesus, central to the claims of the gospel, who Christianity asserts to be the truth of things and who offers a better way of seeing, also in other contexts, the reality of how things are.

From the perspective of the gospel, Jesus, as the logos made flesh in the particularity of history, defines the nature of things and their purpose, giving them meaning. In him we understand the ethical claim made on each one of us. The curious thing about the Christian assertion, however, is that it does not say only that Jesus embodies universal truth and that the story of his life, and especially his death and resurrection, displays this truth lived out by a particular human being – already a remarkable claim. But it says that this Jesus can still be met here and now. The truth is a person, and we can meet him and, since he is the truth of things, we all do in fact relate to him – after all, he is ‘the light of all people’ (Jn 1:4) and the true light ‘which enlightens everyone’ (Jn 1:9). In this personal interaction, this relationship, we encounter the revelation of the nature, purpose, meaning, and consequent ethical claim of the cosmos.

We need now to unpack this ‘nature, purpose, meaning, and ethical claim’. It is rooted in the understanding of who Jesus is. Put at its bluntest: Jesus is God and God present in history. That is to say, with Colossians, that he is ‘the image of the invisible God’ (Col. 1:15), which means that he makes visible the invisible divinity, and so gives us access to understanding who God is. Several things flow from this. Since God is the source of all things, it follows that the true understanding of them lies in God, that is, in how God made them: their ‘nature, purpose, meaning, and ethical claim’ rest in God. If Jesus renders that true understanding visible, then in his very being he renders visible not only the nature of the creator of all but also the nature of what is created. The outflowing of love seen in his life, the readiness to die for the other, all the virtues displayed in Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection are, in a deep way, the nature of all things. All things are made to be love; and this is not just how they are but how, insofar as they have a choice (as with human creatures), they are called to love. Even where love breaks down, and non-loving emerges, that too has somehow to be encompassed by this nature of things as seen in Jesus; and it is. It is encompassed by love in his dereliction on the cross. Here unlove is transformed into love, the defeat of love into its triumph in salvation; the suffering has the purpose, the meaning, of love and, since this death leads to new life in the resurrection, suffering gives way to joy.

For this reason, Jesus is the ‘firstborn of all creation’ (Col. 1:15), since he is the principle that gives rise to everything. Indeed, he is both the ontological foundation of all things, since they ‘have been created through him’, as well as their meaning and purpose, since they have also been created ‘for him’ (Col. 1:16). This can be summarized by concluding, as Colossians does, that ‘He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together’ (Col. 1:17). In other words, he is the truth.

The prologue of the Fourth Gospel offers a very similar picture. Here the logos is the expression of God, the Word that existed before being spoken ‘in the beginning’ in the act of creation. It is distinct from God and yet still God. Through this logos all things were made; he, who as the Word is full of the divine meaning, is the source of all creation, the one who gives it life and guidance: ‘All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people’ (Jn 1:3-4). It is this logos who became flesh in Jesus. Jesus is thus the expression of God, containing in himself the nature, purpose, meaning, and ethical imperative of all things.

The dimensions of truth

The truth of the uncreated and of the created which Jesus is, has several dimensions that have practical implications for us human beings in our struggle to live our lives as best we can. We see this by taking a look at the great Johannine declaration, in response to Philip: ‘I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me’ (Jn 14:6). It is one of the boldest ‘ego ’eime’ statements of the gospel, with resonance with all of them. Like the others it recalls God’s name as the great ‘I am’ revealed to Moses in Exodus 3:14. Saying ‘I am’ Jesus affirms, as he puts it also in the Fourth Gospel, ‘I and the Father are one’ (Jn 10:30). The context, however, defines truth as not just something to be understood but as something to be done. The statement comes in reply to a question about the way of going to the Father, and Jesus identifies himself as the way, indeed, he radicalizes the idea of ‘way’ both by identifying himself as the way and by asserting that he is the only way of coming to the Father. He is the truth about how to find God.[1] The practical import of this is profound. We can only walk this way by, as it were, being Jesus. That is, we have to be ‘Christified’, participate in Jesus’ own being. Living Jesus’ word, living the sacramental life, especially the great dominical sacraments of baptism and the eucharist which incorporate us into Christ, we have ways by which we can embark upon the way to God. Above all we have to be effectively incorporated into the identity of Jesus who, since he is God, is love. Without love any effort to live the word or sacramental communion is simply a waste of time. This already begins to hint at further depths we shall see in the relational nature of truth.

The realization that truth is not just what you understand but is grounded in relationships is emphasized by the next part of the affirmation: ‘I am … the truth’. As David Ford points out:

In the Septuagint and the New Testament the Greek work alētheia (“truth”) not only means what corresponds to fact but also the content of the Hebrew ’emet. This has a broader sense of what, and especially who, is reliable and to be trusted. It is as much about what is done as what is known or believed – belief, cognition, and behaviour are interwoven, as in the truth of a promise.[2]

Throughout the Fourth Gospel, as through the synoptics and the rest of the New Testament, Jesus is depicted as the demonstration of God’s faithfulness, which is to say he demonstrates God’s truth in action as he works for the saving of Israel and, breaking down all barriers, of all the nations. In his person the perceptual and noetic dimensions of truth coincide with its practical and regulatory dimensions.

Jesus is thus the true one who reliably conveys knowledge of what is true. He is the framework and the measure for all other truth. There is no truth beyond him; he is the highest order category to which all other truths must be related ‘whether factual or fictional; conceptual or narrative; quantitative or qualitative; scientific, moral or artistic; intellectual, emotional, or practical’.[3] These other truths are not deprived of their significance or of their necessary autonomy; on the contrary, Jesus’ truth as faithfulness to himself (as God cannot deny himself[4]) means he demands that all other things be faithful to themselves. But his truth also indicates that the meaning of things is love, as he is love. All things exist, therefore, to serve and to be served, each thing an end in itself and a servant of all. Truth, seen in Jesus, defines the reality of the entire cosmos and, at the very same time, enjoins a moral imperative, that of love.

For this reason, he is also life for any who share in him, which is to say, who walk on the way that he is or dwell in the truth that he is. To be love, participating in him, is to have the abundant life, the eternal life, the life from heaven, the very life of God that Jesus is. While the point of access is through belief, that access is made effective in sharing in Jesus: ‘Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood have eternal life, and I will raise them up on the last day, for my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink’ (Jn 6:54-55). We attain true life by our nourishment on the truth, feeding upon Jesus himself and, in particular, by doing so sacramentally in the eucharist. This same life-giving nourishment is also conveyed by the words Jesus speaks (so that we can live them), for ‘It is the spirit that gives life; the flesh is useless. The words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life’ (Jn 6:63).

Behind all these dimensions of truth as the person, Jesus, there is another. It indicates that the nature of truth itself is relational. Jesus is who he is because he is the full, total expression of God, that is, as Jesus puts is shortly after the ‘ego ’eime’ statement we have been considering: ‘Whoever has seen me has seen the Father’ (Jn 14:9). Who Jesus is depends upon his relationship with the Father. Jesus is the self-expression of God in history. We, if we participate in Jesus, are caught up into that selfsame relationship. Hence we may encounter the truth in the person of Jesus, and so in our relationship with him, but for this truth to be active in our lives, for us really to know the truth therefore, we have in union with Jesus to be in relationship with the source of all truth (being, beauty, goodness, life, joy…). Truth is relational not just in our relating to Jesus, but because ontologically, before the existence of all worlds, it is already relational. That is the nature of the Godhead and, indeed, of all that the Godhead has created.

Accessing the truth

The key question then is how do we access the truth? Believing in Jesus, having a relationship with him, participating in his sacraments, living his words (which are the culmination of all the Scriptures and so imply the acceptance of all the Scriptures) are answers that flow readily from what has been said till now. But more needs to be said. It is all too easy for us to have a superficial understanding of our relationship with Jesus and to reduce our sacramental life and our living according to the Scriptures to formal compliance. As we explore further, we shall see how the recognition of Jesus as truth works out in practice.

We need first of all to take seriously what is meant by our dwelling in the relationship between Jesus and the Father. This is something that for Jesus is clearly extremely important, for ‘no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him’ (Mt 11:27). Its crucial importance is indicated in the climactic moment of the Fourth Gospel in John 17. Jesus declares that sharing in this relationship defines his mission on earth since he says that while he was still in the world, he protected his followers in the Father’s name (Jn 17:12), asking that, as he leaves the world, the Father should now protect them ‘in your name that you have given me, so that they may be one, as we are one’ (Jn 17:11). It is this same sharing in the primordial unity of God with Godself that Jesus prays for those followers who come after, asking that they too ‘may all be one. As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us’ (Jn 17:21) and, in a powerful form of Hebrew parallelism, Jesus goes on to specify that he has given his divine glory to them ‘so that they may be one, as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one’ (Jn 17:22b-23a). Living in unity is thus sharing together in the life of God. It is God present and active in the here and now. This is dwelling in the Truth. No wonder that the result is a powerful witness to the reality of God and leads other people not only to believe but to know by experience (see Jn 17:23)[5] that Jesus has been sent by God. Witness is given to the Truth because the Truth has become a living experience.

Far from competing with truth, when unity is of this quality, a mutual dwelling in God, it is the display of truth. Living in unity gives us the opportunity, should we ever dare to take it, of discovering truth. How sad that so often people, even Christ’s followers, destroy relationships with the aim of preserving truth!

Of course, the whole thing depends on what kind of relationships we are speaking about. It is the quality of our relationships that allows them to be (or forbids them from being) a sharing in God. It is not enough to have good intentions, to mean well and even to hope sincerely for the good of the other. The quality of love has to be the quality of love in God, a welcoming into ourselves of the manifestation of God’s own being (that is, his glory). Perhaps the most important gloss to give to this unity is Jesus’ own New Commandment: Love one another as I have loved you (see Jn 13:34 & 15:12). This is how he defines love: as patterned on his death on the cross. Love has never been defined like this before: cruciform. Love lived in God is born in death.

When there is this love we dwell in God together and have his light. We are in God and God is among us. In Matthew 18:20 Jesus announces the same principle using slightly different terminology. Here, in reference to the almighty prayer of those in agreement (that is, in unity), he says, ‘Where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them’. In his name means in his identity, that identity which is displayed in its fullness on the cross. The result of our living in his identity is dwelling in God; in other words, through being united with Jesus, we dwell with God, because the God-who-is-human is among those gathered in this way. Speaking in these terms Matthew’s Gospel gives emphasis to another dimension of the unity spoken of in John 17: it brings us into the presence of the living Christ – that Christ who dwelt in Palestine two thousand years ago and now is risen and dwelling in glory. It is he who enlightens our minds and warms our hearts, as he did with the disciples on the Emmaus Road (see Lk 14:32). Our unity, therefore, gives us access to truth because through our dwelling together in the truth, in the person of Jesus, he gives light to our minds.

Returning to a Johannine framework, we can see the trinitarian dynamic present in this experience of access to truth. Jesus makes a pledge for the future that we will be guided ‘into all the truth’ (Jn 16:13) by the Spirit for he will not speak on his own but ‘will take what is mine [that is, of Jesus] and declare it to you’ (Jn 16:14). Then, in a trinitarian flourish, he points to the source of truth in God, saying, ‘All that the Father has is mine’ (Jn 16:15). It is the Spirit at work in the enlightening of our minds, so as we dwell through our unity in the relationship between the Father and the Son, it is he who gives us access to the truth, to a deeper knowledge of Jesus. Which should come as no surprise, given that the Spirit is the relationship, the mutual love, uniting the Father and the Son. Growth in relationship means growth in our access to truth. Human relationality when lived in God grants access to that which is the case about the nature, purpose, meaning, and ethical claim of all things.

Beyond dialogue

But we need to be able to live properly in the cruciform love that allows us to enter into the cognitive aspect of human relationality. This alone keeps us in God and frees our minds to receive God’s light. Among the many principles that could be adduced, I would suggest three as key so that our thinking together may be the practice of thinking as love.

Relational. In the first instance we need to grasp that while truth in itself is absolute, because God is truth, truth as we perceive it is partial because we grasp only some of it in our relationship with God. What we perceive will be true, but it will also always be partial given our creatureliness. We are finite and can only perceive so much. Therefore, we need constantly to learn and to learn from others. Even Jesus, as a thinking human being, had to learn. We too need to learn from others, a statement that may seem obvious but is not if we consider its radical implications. For if the other person too has a partial, but real, grasp of the truth we need to listen to it fully, even if it appears to contradict what we hold dear. Likewise, when we offer our understanding to the other it can never be the imposition of our point of view because the lack of respect implied by imposition not only destroys love, but it does not allow that the other may have a valid perception which our imposition would crush. Of course, the other may be mistaken, as we may be, but that can only be discovered as we discern the truth together.

Detached. To achieve this, we need to be able to dispossess ourselves of our partial truth, which does not mean thinking either that it is wrong or that we have to abandon it. We have to be able to set our understanding aside sufficiently to be able to see things as the other person sees them. We do not cling on to our perception as if it were the only truth, allowing ourselves to be challenged by the possibility of a new or unthought-of perception and, at the same time, allowing the other person the freedom to discern the truth at their own pace and in their own way. Growth in this way of receiving and offering perceptions requires a deepening psychological and spiritual maturity, but the flourishing of love that it occasions means that our thinking can really be practised as a participation in God because it has the nature of love.

Open to Surprise. If we have thought together in love, there comes a moment when the Spirit opens our minds to a new perception of truth. It will necessarily share in the limitedness of all our perceptions, but it will carry conviction. It will be a surprise, most often something new that was not present, at least in this way, in the minds of those who are seeking the truth together. It may even be similar to the original thought of one of the conversation partners, but it will also be seen afresh, in a new light. No party will feel vanquished because the surprise of the new thought is owned by all. Hence, within the all-important realm of the interpretation of Scripture by Christians this way of thinking provides a further hermeneutic possibility. By letting ourselves be converted by Christ so that we think in him, with him, we let our meeting with him in our living unity guide our minds. Christ himself, Truth himself it may be better to say, shows us his own meaning in the written word: the Word interpreting the word. For us the task remains to have the courage to remain united, in a cruciform love, through all the moments of darkness, uncertainty, and challenge, until finally we all perceive together, in a divine surprise, the truth we now share.

These three characteristics guarantee that the shared process of thought is undertaken in love. The process is clearly a dialogue, and it is structured to seeing ‘that which is the case’. Yet its demanding ascesis takes us beyond dialogue, and the discovery as it were of facticity, to the dimension of truth in the deepest sense discovered together. This is not a negotiation leading merely to compromise; however much compromise may be useful in some circumstances, but a dwelling with each other in God in unity that allows God to reveal a new understanding. Above all, demanding as it may be, it is possible to be put into practice. The opposite of a mini war, such thinking as love does not share in the defects of debate as conflict, even though it may use the dialectical process of debate. Consequently, this relational process will always benefit from employing logical clarity, or the use of imaginative reasoning, or appeals to due authority, or the expertise of the participants, or any other method of sharpening the mental functions and cognitive capabilities of those who engage in it. But it needs one thing in particular, especially when the process deals with a tough topic: the increase of cruciform love.

Conclusion

Thus it becomes clear that truth is relational in several senses. It is relational because the way to achieve it is via human relationships lived in God. But it is relational because whatever is understood is always a perception in relation to God, the only absolute. And it is relational because the nature of God, the nature of the absolute, is relational. We can only begin to imagine the impact that a practice of truth-seeking based on this relationality would have. Within the various churches, it would provide a way of meeting Christ and of finding his truth that enlightens the meaning of the Scriptures with the potential of taking us beyond the often harmful debates that are, in effect, constantly with us as history progresses and new questions arise. Among the churches it would give the possibility of genuine reconciliation and the shared discovery of Christ’s truth in all the various ways, the multiform richness, in which it can be perceived. Indeed, it should be said that seeking truth in unity gives new dignity to Christian ecumenism. For Anglicans, and in particular for members of the Church of England rent by so many disputes, the way of unity could prove an unexpected opportunity not so much for simply staying together but, more to the point, for solving the very issues that drive so many apart. The possibilities for dialogue with those of other faiths and with those of no specific religious affiliation are exciting should we be able to embark upon a similar journey of discovery together. And what is more, all the disciplines of science and the arts enquiring by their own methods into reality could, with the light of Christ shed through the relationship among people who love, be enhanced and assisted in finding the particular kinds of truth that each has the task of seeking. And, who knows, perhaps these disciplines too will shine that same light back with new intensity upon our understanding of Christ, upon our grasp of the beauty of God?

[1] It is possible to read this as presenting an exclusivist Christ. Nonetheless, the sense in the Prologue of John of the logos reaching everyone and the unconditional love propelling Jesus to give his life for the redemption of all (‘And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself’ Jn 12:32) would rather indicate an inclusivist interpretation. All in the Old Testament who relate to God and all those outside the Chosen People who come to God are doing so through Christ, whether or not they have an explicit knowledge of him.

[2] David F. Ford, The Gospel of John: A Theological Commentary (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2021), 275-76

[3] The Gospel of John: A Theological Commentary, 277.

[4] ‘If we are faithless, he remains faithful—he cannot deny himself’ (2 Tim 2:13).

[5] The word used for knowledge in John 17:23 (‘that they may become completely one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me’), ginōskōsō, does not only mean head knowledge but knowledge gained by experience, the effort to learn, and the ability to recognize something for what it is.